Despite boasting significant strides in improving literacy rates over the past few decades, India continues to grapple with the complex reality of functional illiteracy. This paradox where individuals may be deemed literate by statistical standards yet lack the skills to engage meaningfully with written information constitutes the core of what can be termed the “literacy illusion.” While national surveys and census data proudly report rising literacy figures, a deeper examination reveals vast disparities in quality, access, and applicability of education, particularly among women, marginalized castes, and rural populations. This essay explores how the phenomenon of hidden illiteracy persists beneath the surface of official literacy, shaped by socio-economic inequality, gender bias, and institutional shortcomings.

India’s Census 2011 recorded an overall literacy rate of 74.04%, a considerable increase from 64.83% in 2001 and a dramatic rise from just 18.3% in 1951. However, the criteria used to measure literacy defined merely as the ability to read and write with understanding in any language fail to account for the quality, consistency, or utility of that literacy. In practice, millions of individuals who meet this minimal criterion are unable to comprehend written instructions, fill out basic forms, or interpret information in newspapers and official documents. According to the Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) 2022, while over 95% of children in the 6–14 age group were enrolled in school, only 20.5% of grade 3 students in rural India could read a grade 2-level text, and basic arithmetic proficiency also remained alarmingly low (ASER Centre, 2022). This mismatch between school enrollment and actual learning underscores the hollowness of India’s literacy triumph.

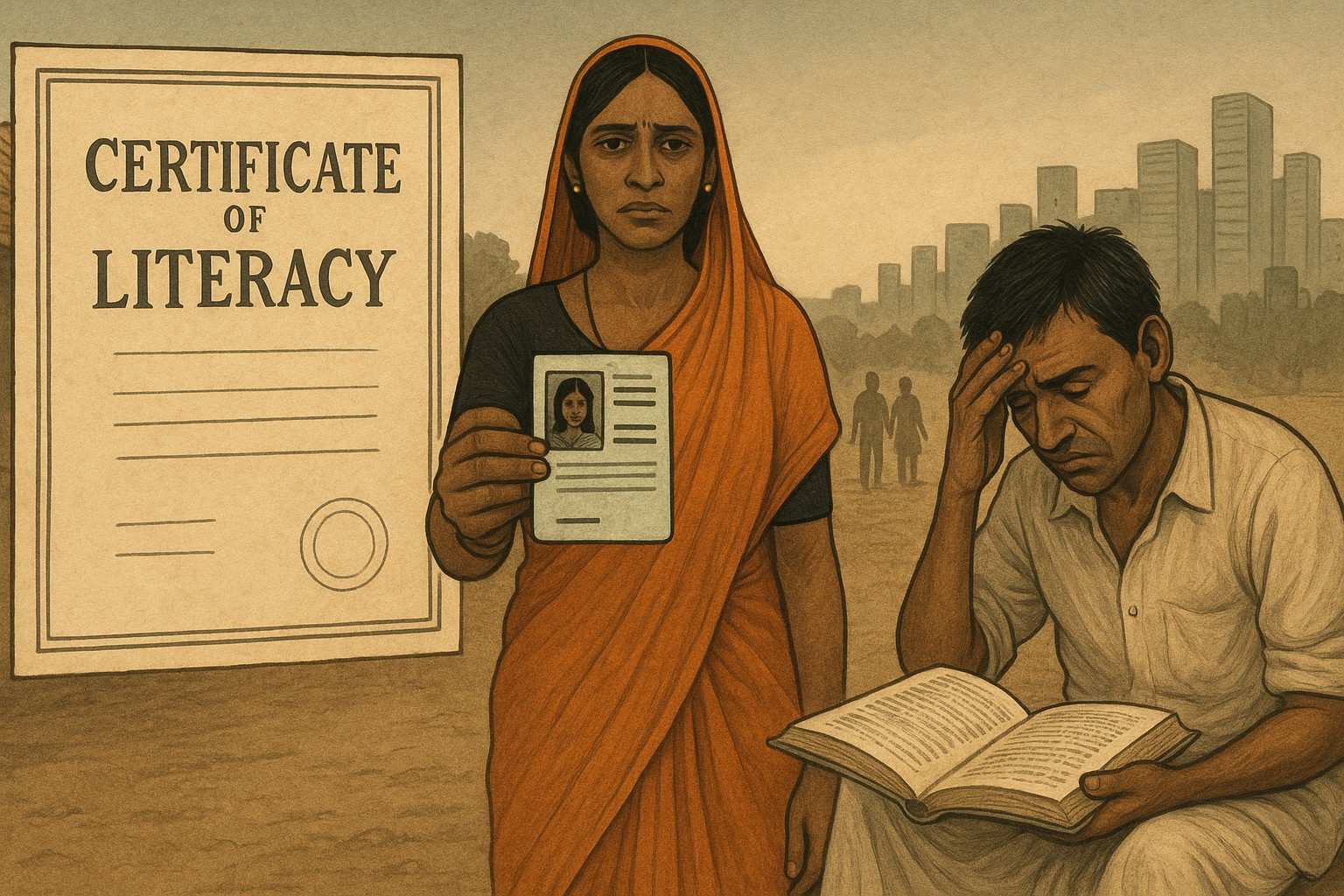

The illusion of literacy is further magnified when viewed through the lens of gender. Although the gender gap in literacy has narrowed, it remains significant. As per the 2011 Census, male literacy stood at 82.14% compared to female literacy at 65.46%. More troubling, however, is the functional illiteracy embedded within these figures. Many women who are declared literate may have received only intermittent schooling, often in environments lacking adequate teaching materials, trained staff, or safe and inclusive spaces. In communities where early marriage and domestic responsibilities interrupt education, literacy does not translate into empowerment or autonomy. These women are often unable to read prescriptions, navigate public health information, or access government welfare schemes, thereby remaining excluded from the very systems literacy is meant to unlock.

Caste and socio-economic status add additional layers to the problem. Children from Dalit, Adivasi, and other backward communities often attend under-resourced schools, are taught in a language that may not be spoken at home, and face systemic discrimination that discourages classroom participation. These factors culminate in a cycle of low comprehension and high dropout rates, especially in rural India. Government initiatives like the Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan (Education for All) and the Right to Education Act (2009) have improved infrastructure and enrollment, but the qualitative aspect of education continues to suffer due to poor teacher training, absenteeism, rote learning methods, and overcrowded classrooms.

The literacy illusion also extends into urban areas, though in different forms. While cities have higher average literacy rates, urban slums and migrant communities remain deprived of formal schooling or are trapped in substandard private schools with little to no regulation. Furthermore, digital literacy is now a vital component of functional literacy in the 21st century. With the government’s push toward digitization, especially in services like banking, health, and governance (e.g., e-Shram portals, Aadhar-linked accounts), lack of digital skills has created a new underclass of the “new illiterates” those unable to navigate basic smartphone apps or online portals despite being “literate” by traditional measures.

The result is a crisis of comprehension: a nation where millions possess a literacy certificate but lack the cognitive tools necessary to translate that ability into livelihood, civic participation, or personal growth. This situation has serious implications for democracy, development, and social justice. For instance, citizens unable to interpret government policies or vote independently remain susceptible to manipulation and exclusion. Women who cannot read legal documents or health advisories are less likely to access justice or prenatal care. The economic cost is equally staggering, as functionally illiterate adults are often restricted to low-paying, unskilled labor, perpetuating cycles of poverty.

To dismantle the literacy illusion, India must shift from a narrow focus on enrollment and basic reading toward a more nuanced understanding of functional, critical, and digital literacy. Education policies must be realigned to emphasize comprehension, critical thinking, and life skills rather than mere syllabus completion. Investments in teacher training, multilingual pedagogies, inclusive curriculums, and community-driven adult education programs are essential. Furthermore, periodic and transparent assessment tools like ASER must inform policy decisions and resource allocation, ensuring that literacy is not just counted but truly cultivated.

In conclusion, while India’s rising literacy rates are often celebrated as symbols of progress, the reality is far more complex. Hidden beneath the surface of these numbers lies a vast landscape of exclusion, where millions are literate in name but not in ability. Addressing this illusion requires a fundamental rethinking of what it means to be literate in a rapidly changing, information-driven society. Only then can India move toward a truly empowered and equitable future.

– Dr. Priyanka Singh Assistant Professor

Humanities and Social Science, Madhav University